Is Power of Siberia 2 a white elephant?

What is the economics and the politics around the troublesome gas pipeline from Yamal to China?

The Russian-European energy war left hundreds of billions of cubic meters of natural gas stranded in the gas fields of the Russian Yamal-Nenets province. Is it possible to profitably sell these volumes to China? Would it be an adequate replacement for the lost European markets? What is the possible time frame for the start of deliveries after Russia and China sign the deal?

2022 was the end of the era, that started 55 years before that, when the newly-built Brotherhood pipeline delivered Soviet gas to Czechoslovakia, a year later – to Austria, and in 1973 to West Germany. This trade allowed USSR and then Russia to monetize vast gas reserves of the Yamal province in the northwestern corner of Asia. Over the years USSR and Russia have invested many billions of roubles and dollars into the gas fields and evacuation infrastructure. The gas province that still has enough resources to keep producing for several decades at the current rates, if not longer, became a stranded asset.

Russia made the first move in the gas war by severely limiting its gas sales to Europe under a number of thinly veiled technical and commercial pretenses, trying to force Europe to abandon its support of Ukraine. But the writing was already on the wall for the prospects of Russian gas in Europe. In the Summer of 2021, EU has announced its Fit for 55 plan, which called for a 1/3 reduction in natural gas consumption by 2030. Immediately after the beginning of the war, the EU drafted plans to reduce Russian gas imports by 2/3 before the end of 2022, and cut them off completely as soon as possible after that, probably by 2025, so Gazprom’s move just accelerated the inevitable.

Despite all of the denial and ridicule of the European Green Deal by Gazprom management, it was becoming increasingly clear that at least some of the Yamal volumes might end up stranded, so Russia was contemplating additional export outlets for Yamal gas, and China was an obvious answer. A pipeline to China from Yamal was discussed for many years without much success, but in 2022 this option has become a firm necessity. Many investments Russia has made in the last decades to expand its exports to Europe and build controlled export routes are now stranded for many years if not forever, but these are sunk costs, some of them literally, as in the case of the blown-up Nord Stream pipeline.

Russia sold 165 billion m3 (bcm) of gas via pipeline to Europe in 2019. Currently discussed capacity of Power of Siberia 2, as the Yamal-China pipeline is called, is 50 bcm, so there is a significant volume reduction. But what is the comparative unit value of the lost sales to Europe and prospective sales to China?

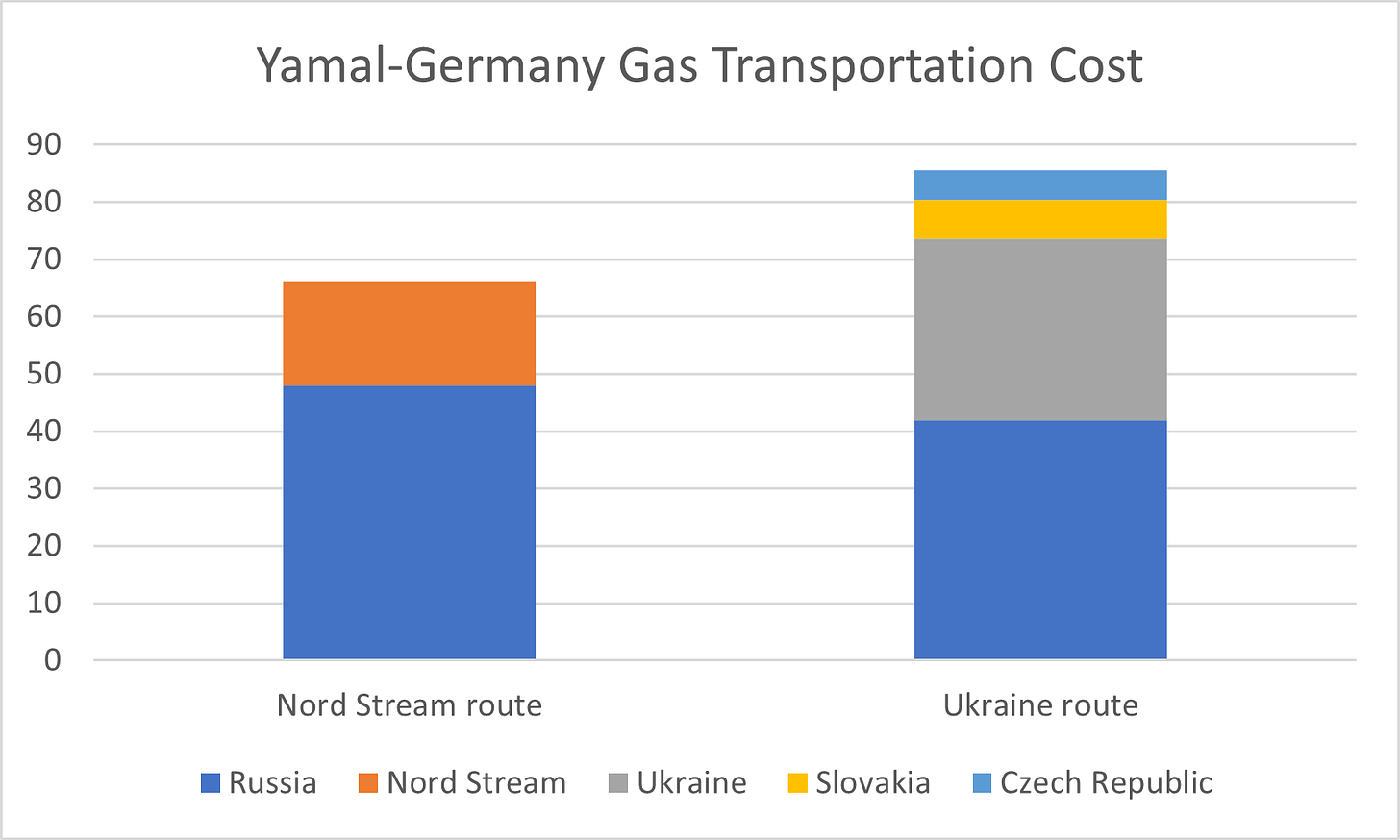

We are going to use the economics of sales to Germany as a proxy for the whole European trade. In the period of 2015-2019, the average import price for gas for Germany was 17.54 EUR/MWh or $220 per thousand m3. During the same period, Brent price averaged at $57/bbl. The delivery cost of gas from Yamal to Germany was comprised of the in-Russia part and the tariffs paid to either Nord Stream or Ukrainian, Slovak and Czech gas transportation companies. There was also a route via Poland, but the tariffs on Polish and Belorussian sections were set up to cover operating expenses only and thus cannot serve as a valid basis for comparison.)

Data sources1

Resulting netback to Yamal for these two routes was $135-155 per 1000 m3 before tax and export excise.

Assuming a long-term price scenario for Brent at $60/bbl, the pricing formula for the original Power of Siberia contract produces the price of $170 per thousand m3. But what might be a reasonable cost of transportation from Yamal to China?

The length of the Power of Siberia route is 2600 km via Russia and 950 km via Mongolia. Let’s assume that both segments will be built by Gazprom and its contractors and will have similar tariff structure. In reality, Russian segment may have a different tariff with true cost spread over increased system-wide tariffs and imposed on Russian consumers, but for the benefit of the analysis let’s assume that there is a separate pipeline project with proper standalone economics. Nord Stream, which had international oil companies as shareholders, and Balkan Stream, a pipeline built and operated in Bulgaria by BulgarTransGaz as a continuation of Turkish Stream may serve as a reasonable benchmark to derive distance tariffs from pipeline costs. Costing of Power of Siberia 2 is based on the costs of the original Power of Siberia, scaled up for the higher capacity and longer length of the PS2. The relationship between the unit tariff and the unit cost on the two European pipelines is then used to estimate the transportation cost through the two Power of Siberia pipelines. In practice, this cost might be slightly lower due to the lower cost of the fuel gas used to power the pumping stations.

Data Source2

Bottom-up calculations using a cashflow model of the pipeline, confirm that these tariffs provide 12% rate of return on the capital, which is in the upper range of returns required for a midstream project.

This unit tariff would mean that the total cost of transportation from Yamal to the Chinese border would be $97 per thousand m3, resulting in a netback of $73 per 1000 m3, compared to $135-155 from sales to Germany in 2015-2020, but if Gazprom could somehow keep the costs under control and build the pipeline on the land at the same unit cost as offshore Nord Stream, bringing the tariff down to $2 per 100km per thousand m3, the netback could go up to $100/1000 m3.

A consensus on the gas upstream cost in the legacy gas-producing regions, which served as the base for the gas trade with Europe, was $15 to $25 per 1000 m3, or $0.40 - $0.65 per mmBTU, excluding mineral extraction tax. Regulated price for the industrial consumers in gas-producing regions is ~$40 per thousand m3, or $1/mmBTU, however, independent producers, not bound by the regulated prices, tend to sell at a discount.

With that in mind, Power of Siberia 2 could unlock $2.5 – $4.3 billion per annum of natural resource rent extraction potential. (The rent is calculated on top of the reasonable rate of return earned in gas production and transportation activities, taken into account in the upstream and midstream (transportation) cost calculation). This is a far cry from the $20 bln per annum rent lost from the sales to Europe, but still material.

Taking standard Russian tax treatment of gas production and exports into account would change the picture – the running rate is 15% mineral extraction tax and 30% export duty, combined they would comprise $76.50, which might leave Gazprom in the red already after transportation costs, but the government would be very likely to cut a tax break for this project, as it did for the upstream projects feeding the original Power of Siberia, however, as we can see, the tax break does not have to be too generous to make the project reasonably profitable.

This analysis also shows that Power of Siberia 2 is not a white elephant, but a viable project. In reality, the costs might be substantially lower, compared to the unit costs of the original Power of Siberia. For the first 1500 km PoS-2 could follow the corridor of the existing pipeline all the way to Tomsk, which would substantially reduce the cost of the route preparation, and from Tomsk to the Mongolian border at Kyakhta and onwards to Beijing it would go along the Trans Siberian Railway, which would also provide some savings.

From the point of view of «Russia, Inc», the real economic costs might be even lower, considering that the works would be performed by the Russian pipeline construction companies, the pipes would come from Russian mills, made from Russian steel, produced from Russian iron ore and coal in Russian steel plants, and all these industries lost their markets after the 2022 and find it difficult to find alternatives, therefore the value of these inputs might be taken into calculation not at the market value, but at the short-run marginal costs.

With this industrial capacity available, and judging by the PS1 precedent, Russia would be able to lay the pipeline in 5-6 years, or maybe even faster, by building several segments of the pipeline in parallel. There might be a competing call on Russian pipeline construction capacity from a desire to expand to oil pipeline to the Pacific Ocean, but this is a less urgent need, so it might have to wait, and there is no firm project for such an expansion.

The main challenge that Russia might face in building the pipeline is the equipment for pumping stations. Russia has a limited production capacity for manufacturing gas turbines used as power sources for pumping stations, and this capacity is also needed for making aircraft engines for the Russian-made air fleet needed to replace Boeings and Airbuses by the end of 2020s.

Pumping stations availability might become the main factor defining the tempo for reaching planned export levels. Usually this is controlled by the drilling schedule of gas fields supplying the pipeline, with upstream gas production growing gradually while the gas field is drilled out. This was the case of Nord Stream 1 and Power of Siberia 1 where ramp-up to full capacity is supposed to take 5 years. But this would not be the case for PS2, as it would tap into fully developed Yamal fields with idle production capacity a few times higher than the proposed PS2 capacity.

It would be interesting to compare the transportation cost via the pipeline to the LNG option.

Two tables in this paper provide a benchmark for unit economics of liquefaction and shipping costs:

US and Qatari projects are the lowest-cost LNG projects in the world, while Yamal LNG is close to the median in terms of its liquefaction cost. Turns out, the pipeline option from Yamal to China ($2.52/mmBTU) is on par with the liquefaction cost of lower-cost LNG projects, and LNG would also have to incur shipping costs as well.

On the pure project economics grounds Power of Siberia 2 might be a good project. However, as it does not have a competitive market, but a strong-positioned buyer on the other end of the pipeline, a larger share of the value might have to be transferred to the captive buyer from the supplier.

Chinese negotiators have a strong hand in these negotiations, the oil-linked formula still leaves some value to Gazprom which does not have any other viable options, thus there is not much negotiation leverage that Gazprom could employ to get better terms.

China’s next best option is gas from Turkmenistan which is still substantially cheaper than LNG. Galkynysh field is quite young and can support a much higher plateau than both its current and currently planned production levels and the only concern China might be having for that source is the principle of diversification and not relying too much on one supplier, but in the meanwhile, it could easily afford to wait and play Turkmenistan against Russia and wait for additional couple years for a new wave of LNG supply from the US and Qatar to hit the market, bring prices down and make Russia and Turkmenistan more pliable.

Another potential pitfall for the economics of the PS2 is the offtake levels and stability of demand. Most of the cost of the project are fixed upfront costs, which hopefully would be recouped over 20 years of work at full capacity. China energy forecasts, even the ones assuming the most ambitious deployment of renewable energy sources, have gas demand growing at least until 2040 and stay relatively stable after that for at least a decade, with renewables mostly replacing coal. However this forecast may change both in the optimistic and pessimistic scenarios for China’s economy, in the first case the country might accelerate its switch to renewables at the expense of gas, and if the economy sputters, it might prefer to stay with dirtier but cheaper coal.

On the other hand, overland gas supply from China-dependent Russia might serve as an additional element of China’s energy security, if maritime supply routes become vulnerable or in the event of a trade war with the West.

There might be a temptation to compare the construction of the Power of Siberia 2 to the construction of the original Brotherhood and follow-up Urengoy-Pomary-Uzhgorod pipeline of the 1960s – 1980s and claim that this is a new page in the glorious history of the Russian gas industry and gas exports. The problem is though, that in the 1980s the prospects of Russian gas sales to Europe looked endless, and as history has shown there was indeed a lot of scope for market expansion. However, the Russian-Chinese gas trade most likely has an expiry date and might be over by 2060 due to the energy transition, and the switch to renewable energy away from fossil fuels, and this outlook leaves little upside to a fresh long-term gas export project.

In the current circumstances with the limited options that Russia has created for itself, the construction of Power of Siberia 2 looks like a sound decision, that might make sense even before the war, but it does not fully replace the value and the volume of the lost European markets and does not create any options and upsides for the future, unlike the Soviet-era pipelines.

Приказ Федеральной службы по тарифам от 8 июня 2015 г. N 216-э/1

"Об утверждении тарифов на услуги по транспортировке газа по магистральным газопроводам ОАО "Газпром", входящим в Единую систему газоснабжения, для независимых организаций" Приказ Федеральной службы по тарифам от 8 июня 2015 г. N 216-э/1 "Об утверждении тарифов н... | Система ГАРАНТ (garant.ru)

https://pulaski.pl/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Raport_NordStream_TS-1.pdf