Flying from shadow into the light,

She is herself both shadow and light.

Arseny TarkovskyA week ago I published a study on the demographics of the global tanker fleet - it is on the Carnegie website.

I have assembled a data set that covers pretty much all of the marine movements of crude oil in 2023-2024, and with this data I could compare the fleet that serves Russian crude oil trade with the global tanker fleet in general and some subsets of it. I wanted to check if the Russian sanctions-defying fleet is really excessively old and whether it really creates a much higher risk of oil spills. Please take a look at the original article, if you have not seen it yet, there are some interesting discoveries.

But I just can not leave my data set alone and have one esprit d’escalier moment after another, more questions to ask, more hypotheses to check.

So, here is a bonus track for my faithful Substack readers.

Most of the oil leaving Russian ports is Russian, it’s the oil produced by Russian companies in Russia, sold by Russian companies and it is subject to the price cap regime, which these companies try to defy with the help of the (in)famous “shadow fleet”. But there are two exceptions. There is the CPC pipeline, that goes from Kazakhstan to Novorossijsk and predominantly carries the oil from Tengiz, Karachaganak and Kashagan oil fields, operated by the Western companies. This oil is sold by the Western majors, such as Shell, Exxon, ENI etc. There is a tiny amount of oil injected into CPC in Russia, but the volumes are minuscule. Another exception is the so-called KEBCO blend. KEBCO stands for Kazakh Export Blend Crude Oil, and the acronym is a derivative of REBCO - Russian Export Blend Crude Oil, which is the official name of Urals. KEBCO did not exist until two years ago. Some of the Kazakh oil is being exported from the landlocked country via Russia. This oil is being mixed into the huge black box of the Transneft pipeline system and loaded into the tankers from the same tankfarms, on the same berths as Urals. It is Urals, no test would be able to tell one from the other, but with an important distinction - it is not subject to any restrictions or price caps, hence it has its own grade name.

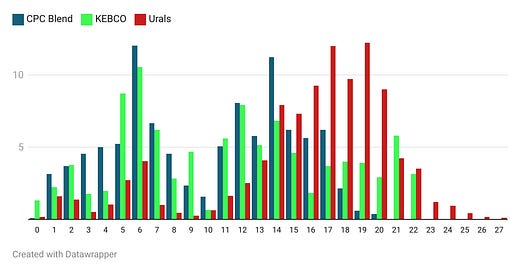

CPC and KEBCO don’t need to travel on shadow fleet tankers, they are not subject to any restrictions that require circumvention. So, it’s interesting to compare the age of the tankers that carry CPC and KEBCO grades vs. those that carry the Urals.

Well, here it is:

The CPC-carrying fleet is the youngest, and the Urals-carrying is the oldest. Statistically. No surprises here. What might be surprising (as was also discussed in the original article), is how much overlap there is. There are quite young ships involved in the Urals trade, there is a sizeable number of 15+ and older tankers lifting CPC crude, and there are plenty 20+ tankers shuffling KEBCO around.

This is just re-iterating what I have already shown, but it’s the case where we can look precisely at the effect of the price cap regime and crude owners on the choices of the tanker fleet composition, with everything else staying the same.

Very interesting, Sergey, thank you for sharing. I hope you'll do more on Substack.